udev

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (November 2014) |

| Developer(s) | Greg Kroah-Hartman and Kay Sievers |

|---|---|

| Initial release | November 2003 |

| Stable release | 257.1[1]

/ 19 December 2024 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Linux |

| Type | Device node |

| License | GPLv2 |

| Website | Official website |

udev (userspace /dev) is a device manager for the Linux kernel. As the successor of devfsd and hotplug, udev primarily manages device nodes in the /dev directory. At the same time, udev also handles all user space events raised when hardware devices are added into the system or removed from it, including firmware loading as required by certain devices.

Rationale

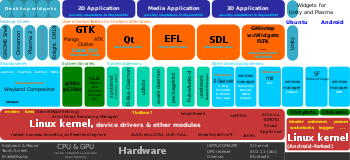

[edit]It is an operating system's kernel that is responsible for providing an abstract interface of the hardware to the rest of the software. Being a monolithic kernel, the Linux kernel does exactly that: device drivers are part of the Linux kernel, and make up more than half of its source code.[2] Hardware can be accessed through system calls or over their device nodes.

To be able to deal with peripheral devices that are hotplug-capable in a user-friendly way, a part of handling all of these hotplug-capable hardware devices was handed over from the kernel to a daemon running in user-space. Running in user space serves security and stability purposes.

Design

[edit]Device drivers are part of the Linux kernel, in which their primary functions include device discovery, detecting device state changes, and similar low-level hardware functions. After loading a device driver into memory from the kernel, detected events are sent out to the userspace daemon udevd. It is the device manager, udevd, that catches all of these events and then decides what shall happen next. For this, udevd has a very comprehensive set of configuration files, which can all be adjusted by the computer administrator, according to their needs.

- In case a new storage device is connected over USB, udevd is notified by the kernel and itself notifies the udisksd-daemon. That daemon could then mount the file systems.

- In case a new Ethernet cable is plugged into the Ethernet NIC, udevd is notified by the kernel and itself notifies the NetworkManager-daemon. The NetworkManager-daemon could start dhclient for that NIC, or configure according to some manual configuration.

The complexity of doing so forced application authors to re-implement hardware support logic. Some hardware devices also required privileged helper programs to prepare them for use. These often have to be invoked in ways that could be awkward to express with the Unix permissions model (for example, allowing users to join wireless networks only if they are logged into the video console). Application authors resorted to using setuid binaries or run service daemons to provide their own access control and privilege separation, potentially introducing security holes each time.[3]

HAL was created to deal with these challenges, but is now deprecated in most Linux distributions, its functionality being replaced by udevd.

Overview

[edit]Unlike traditional Unix systems, where the device nodes in the /dev directory have been a static set of files, the Linux udev device manager dynamically provides only the nodes for the devices actually present on a system. Although devfs used to provide similar functionality, Greg Kroah-Hartman cited a number of reasons[4] for preferring udev over devfs:

- udev supports persistent device naming, which does not depend on, for example, the order in which the devices are plugged into the system. The default udev setup provides persistent names for storage devices. Any hard disk is recognized by its unique filesystem id, the name of the disk and the physical location on the hardware it is connected to.

- udev executes entirely in user space, as opposed to devfs's kernel space. One consequence is that udev moved the naming policy out of the kernel and can run arbitrary programs to compose a name for the device from the device's properties, before the node is created; there, the whole process is also interruptible and it runs with a lower priority.

The udev, as a whole, is divided into three parts:

- Library libudev that allows access to device information; it was incorporated into the systemd 183 software bundle.[5]

- User space daemon udevd that manages the virtual /dev.

- Administrative command-line utility udevadm for diagnostics.

The system gets calls from the kernel via netlink socket. Earlier versions used hotplug, adding a link to themselves in /etc/hotplug.d/default with this purpose.

Operation

[edit]

udev is a generic device manager running as a daemon on a Linux system and listening (via a netlink socket) to uevents the kernel sends out if a new device is initialized or a device is removed from the system. The udev package comes with an extensive set of rules that match against exported values of the event and properties of the discovered device. A matching rule will possibly name and create a device node and run configured programs to set up and configure the device.

udev rules can match on properties like the kernel subsystem, the kernel device name, the physical location of the device, or properties like the device's serial number. Rules can also request information from external programs to name a device or specify a custom name that will always be the same, regardless of the order devices are discovered by the system.

In the past a common way to use udev on Linux systems was to let it send events through a socket to HAL, which would perform further device-specific actions. For example, HAL would notify other software running on the system that the new hardware had arrived by issuing a broadcast message on the D-Bus IPC system to all interested processes. In this way, desktops such as GNOME or K Desktop Environment 3 could start the file browser to browse the file systems of newly attached USB flash drives and SD cards.[6]

By the middle of 2011 HAL had been deprecated by most Linux distributions as well as by the KDE, GNOME[7] and Xfce[8] desktop environments, among others. The functionality previously embodied in HAL has been integrated into udev itself, or moved to separate software such as udisks and upower.

- udev provides low-level access to the linux device tree. Allows programs to enumerate devices and their properties and get notifications when devices come and go.

- dbus is a framework to allow programs to communicate with each other, securely, reliably, and with a high-level object-oriented programming interface.

- udisks (formerly known as DeviceKit-disks) is a daemon that sits on top of libudev and other kernel interfaces and provides a high-level interface to storage devices and is accessible via dbus to applications.

- upower (formerly known as DeviceKit-power) is a daemon that sits on top of libudev and other kernel interfaces and provides a high-level interface to power management and is accessible via dbus to applications.

- NetworkManager is a daemon that sits on top of libudev and other kernel interfaces (and a couple of other daemons) and provides a high-level interface to network configuration and setup and is accessible via dbus to apps.[9]

udev receives messages from the kernel, and passes them on to subsystem daemons such as Network Manager. Applications talk to Network Manager over D-Bus.

HAL is obsolete and only used by legacy code. Ubuntu 10.04 shipped without HAL. Initially a new daemon DeviceKit was planned to replace certain aspects of HAL, but in March 2009, DeviceKit was deprecated in favor of adding the same code to udev as a package: udev-extras, and some functions have now moved to udev proper.

History

[edit]udev was introduced in Linux 2.5. The Linux kernel version 2.6.13 introduced or updated a new version of the uevent interface. A system using a new version of udev will not boot with kernels older than 2.6.13 unless udev is disabled and a traditional /dev directory is used for device access.

In April 2012, udev's codebase was merged into the systemd source tree, making systemd 183 the first version to include udev.[5][10][11] In October 2012, Linus Torvalds criticized Kay Sievers's approach to udev maintenance and bug fixing related to firmware loading, stating:[12]

Yes, doing it in the kernel is "more robust". But don't play games, and stop the lying. It's more robust because we have maintainers that care, and because we know that regressions are not something we can play fast and loose with. If something breaks, and we don't know what the right fix for that breakage is, we revert the thing that broke. So yes, we're clearly better off doing it in the kernel. Not because firmware loading cannot be done in user space. But simply because udev maintenance since Greg gave it up has gone downhill.

In 2012, the Gentoo Linux project created a fork of systemd's udev codebase in order to avoid dependency on the systemd architecture. The resulting fork is called eudev and it makes udev functionality available without systemd. A stated goal of the project is to keep eudev independent of any Linux distribution or init system.[13] The Gentoo project describes eudev as follows:[14]

eudev is a fork of systemd-udev with the goal of obtaining better compatibility with existing software such as OpenRC and Upstart, older kernels, various toolchains and anything else required by users and various distributions.

On May 29, 2014, support for firmware loading through udev was dropped from systemd, as it has been decided that it is the kernel's task to load firmware.[15] Two days later, Lennart Poettering suggested this patch be postponed until kdbus starts to be utilized by udev; at that point, the plan was to switch udev to use kdbus as the underlying messaging system, and to get rid of the userspace-to-userspace netlink-based transport.[16]

Authors

[edit]udev was developed by Greg Kroah-Hartman and Kay Sievers, with much help from Dan Stekloff, among others.

References

[edit]- ^ "Release 257.1". 19 December 2024. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ Marti, Don (2 July 2007). "Are top Linux developers losing the will to code?". ComputerworldUK. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Pennington, Havoc (2003-07-10), Making Hardware Just Work

- ^ Greg Kroah-Hartman. "udev and devfs - The final word". Archived from the original (Plain text) on 2011-07-09. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ a b c "systemd/systemd". GitHub. Retrieved 2016-08-21.

- ^ "Dynamic Device Management in Udev" (PDF). Linux Magazine. 2006-10-01. Retrieved 2008-07-14.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "HALRemoval". 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ^ "Thunar-volman and the deprecation of HAL in Xfce". 2010-01-17. Archived from the original on 2017-12-26. Retrieved 2017-12-25.

- ^ Lennart Poettering (2010-04-25). "Relationship between udev, hal, Dbus and DeviceKit?".

- ^ Sievers, Kay (2012-04-03). "The future of the udev source tree". linux-hotplug (Mailing list). Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ^ Sievers, Kay, "Commit importing udev into systemd", systemd, retrieved 2013-05-22

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2012-10-03). "Re: udev breakages". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Retrieved 2014-10-28.

- ^ "gentoo/eudev – README.md". GitHub. Retrieved 2017-12-25.

- ^ "Gentoo Linux Projects – Gentoo eudev project". Archived from the original on 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2017-12-25.

- ^ "[systemd-devel] [PATCH] Drop the udev firmware loader". 2014-05-29.

- ^ "[systemd-devel] [PATCH] Drop the udev firmware loader". 2014-05-31.